How to make your own plan

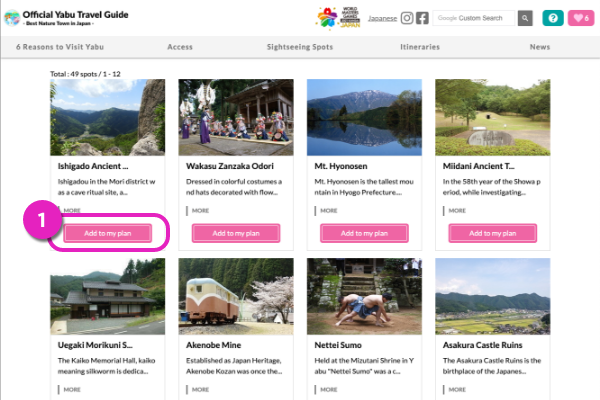

Step 1

Search for places you want to visit

- Add the spots that you are interested in into ”My Plan” (your favorites)

- This can generate a route automatically by looking at the contents of ”My Plan”.

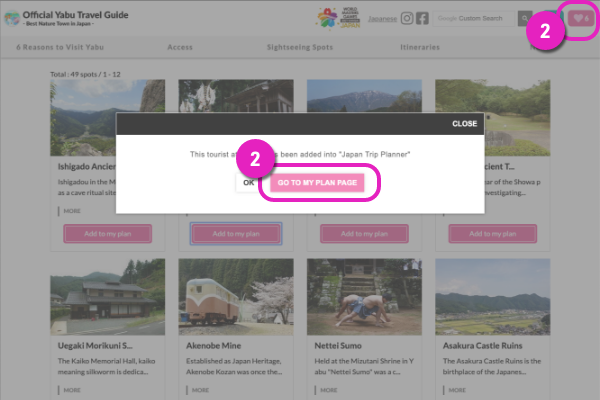

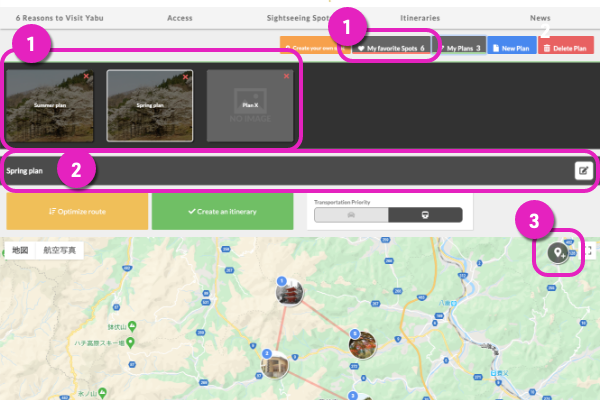

Step 2

Make a Day Plan!

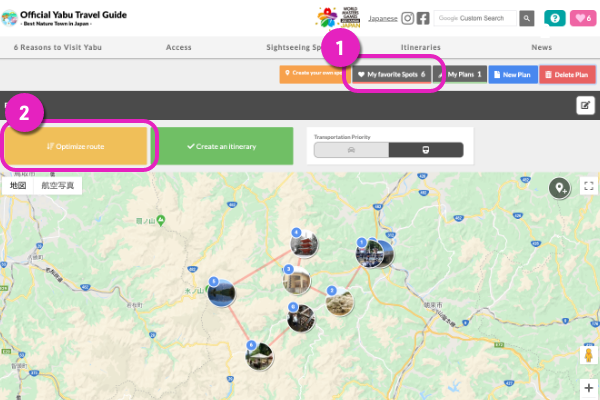

- Using [My Favorite Spots] , you can put places you want to go into your plans.

- Sort in the most convenient order automatically

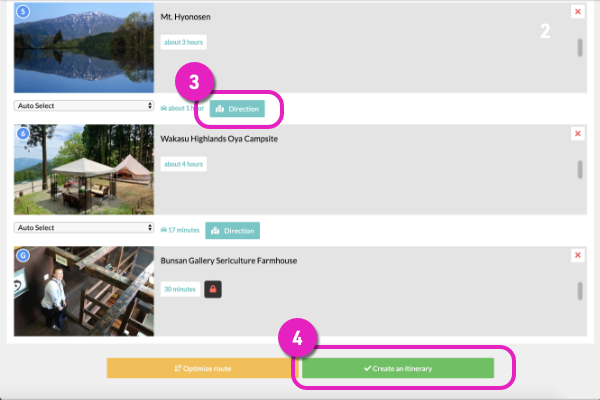

- Check the travel route and time by pressing the ”Direction” button (travel route by train, car or on foot will be shown).

- Create route with the ”Create an itinerary” button.

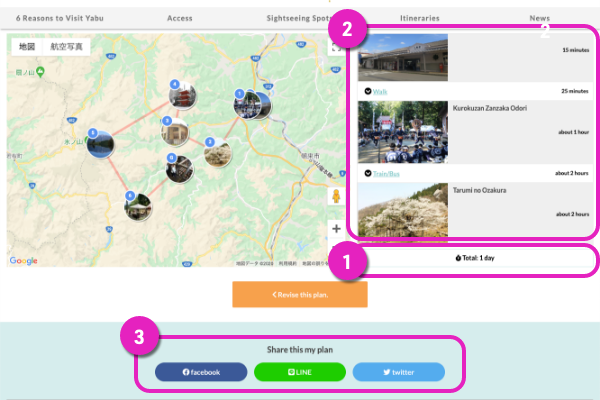

Step 3

Transfer the Plan to your smartphone and head out!

- Show the duration of the route.

- Display the entire route (by foot or by car).

- You can transfer the trip you created to your smartphone or to friends by sharing it on social media or entering your email address and sending it.

As this plan is information that was output to be shared, it will not be deleted even if the original plan is deleted.

- The plans you create will be saved under [My Plans]. Press [Create New Plan] to create a new plan.

- The plan name can be changed using the [Edit] button.

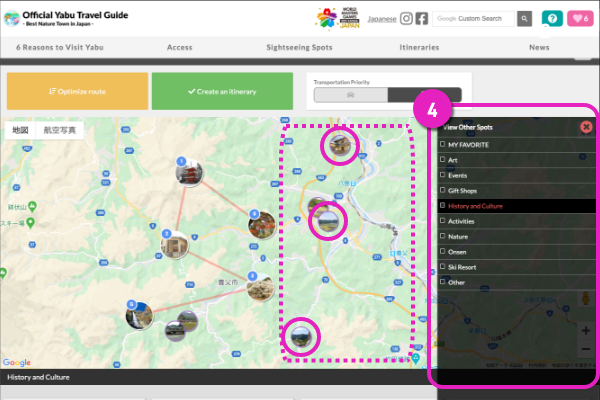

- If you press the [Pin] button, you are able to open the Category menu.

- Add the spots that you are interested in into “My Plan”

Home of wild horses and the birthplace of modern agriculture

Shimosōdaichi in northern Chiba and the Mineoka mountains to the south have long been home to equestrian ranches. Wild horses running free across the land and the livelihoods of local people have helped foster a unique landscape and culture across the land of Bōsō. In recent years horse rearing has given way to agriculture. Along with new crops being produced, the region has also developed to become a leading dairy producer, with dairy farming forming the cornerstone of agricultural activity in Chiba. The land of Bōsō with all its abundance is forever engraved with the entwined history of its people and horses.

Story

01

Story

02

Story

03

Story

04

Story

05

The Beginning of Maki

When horses were brought from the Korean Peninsula to the Japanese archipelago during the Kofun period, the culture of horses also spread to Bōsō. Suitable for breeding horses due to its temperate climate and vast wilderness, horses spread in Bōsō through their use in cavalry, the transportation of goods, farming, religious ceremonies and as land tax. This can be seen though remains such as harnesses and horse-shaped haniwa (clay figures) excavated from archaeological sites and kofun (ancient burial mounds) of Bōsō.

In the Middle Ages, horses became a symbol of bushidan (band of warriors or group of samurai). The military power of the Bōsō bushidan, Bōsō Heishi (Taira clan) and their descendants, the Shimosō Chibashi (Chiba clan), the Sengoku daimyō (Japanese territorial lord in the Sengoku period) Satomishi (Satomi clan) ruling over the Bushidan of Awa were supported by maki and the horses of the Bōsō region.

Kippohachiman no Yabusame

Kenshin Uesugi Usui Castle Attack

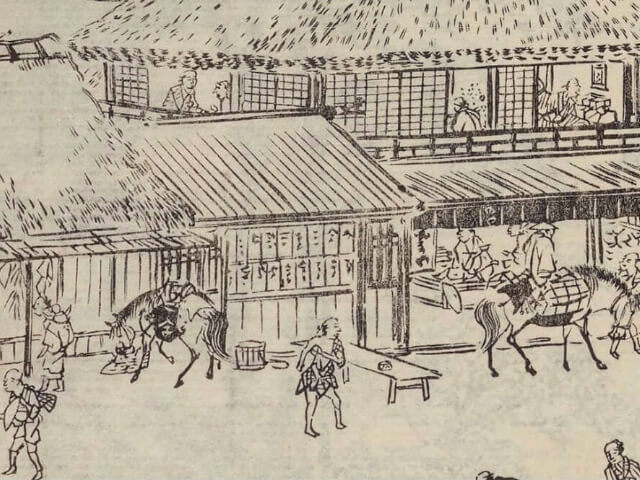

The Maki of Tokugawa Shogun

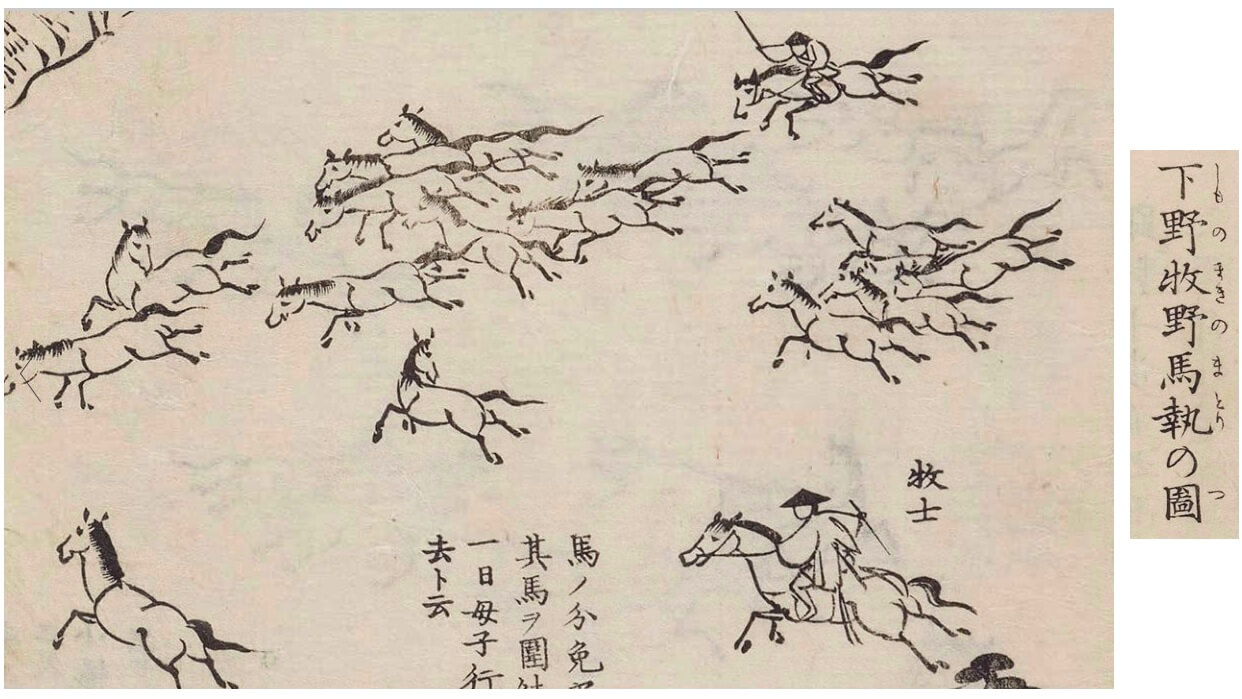

Tokugawa Ieyasu who established the Edo bakufu, worked on the preparation of bamaki (horse pasture) of the Sengoku daimyo Chibashi (Chiba clan) and Satomishi (Satomi clan). Hence, here on the land of Bōsō, the bamaki of Tokugawa Shogun was formed. The bamaki were Three Maki : “Koganemaki” and “Sakuramaki” of Shimosō and “Mineokamaki” of Awa. Koganemaki and Sakuramaki were on the vast flat plains of Shiomōsadaichi and the Moneokamaki was on the ridges and slopes of the Mineoka Mountains. Bamaki were enclosed by embankments and forts with a total combined length of more than several hundred kilometres and up to thousands of wild horses were bred in them.

The shogun ordered Hatamoto (direct retainers of the shogun family) to the position of noma-azukari (general manager of the Three Maki) and the nomazukari had the nomabugyō (governmental official managing maki on the field who bred horses at the maki and sent the good horses to the noma-azukari at the Edo castle) manage the Three Maki. The management offices of kaisho and jinya were placed at the maki and professionals such as mokushi (a governmental post in charge of maintaining pastures), sekomawashi (those who drive horses into a corner), tsunakake (rope fastener), hoshu (catcher) and bai (horse doctor) were working.

Shisui-juku

Former Yoshida Residence

Shimada Chōuemon and Seigorō Residence

The Lives of People Living Alongside Maki

In order to manage the vast maki of Bōsō, a total of about 500 villages called notsukemura were responsible for the maintenance and management of nomadote (an embankment made to manage wild horses) and facilities relating to the capture of wild horses, lookout of wild horses, protection of lost horses, the ridding of wolves and feral dogs, and more.

On the other hand, the wood, wild plants and grass of the vast maki were sold prioritizing the villages surrounding the maki. The maki brought on burdens but also economic benefits to the villages. The repair work of places such as the nomadote which take place in the agricultural off-season, brought in extra income and the people lived in co-exsistence with the maki.

Nomadote (embankments)

Seko (villager) driving horses into tokkome

Fukoku Kyōhei (Rich Country, Strong Army) and Cultivation

In the first half of the Edo period, when the need for military horses began to diminish, the maki (pastures) of Bōsō came to a major turning point. A part of Koganemaki and Sakuramaki of Shimosō were cleared and became Nittamura. At Mineokamaki, Shogun Yoshimune ordered for the commencement of dairy farming for the rearing of cattle and production of dairy products.

In the Meiji era, the maki of Bōsō was abolished and the vast grounds of Koganemaki and Sakuramaki of Shimosō became cultivated land of the unemployed and poor of Tokyo, and were also used as military land, dairy experiment stations and large-scale private farms. It became the land leading in the adoption of Fukoku Kyōhei (Rich Country, Strong Army) of the new Meiji government.

Former Mizuta Residence

Sanrizuka Imperial Pasture Memorial Hall

The Birthplace of Modern Agriculture “The Agricultural Kingdom of Chiba”

With the dawn of the Meiji era, the maki of the Tokugawa Shogun was abolished and the Koganemaki and Sakuramaki of Hokuso were cleared. Through the persistent efforts of several generations, the land of Hokuso was reborn and became Japan’s national leading farmland, producing pears, peanuts, watermelon, sweet potatoes and more. With the breeding of animals such as sheep and Western horses, as well as facilities for veterinary medicine placed on the land, it also became the pioneer of modern dairy farming.

At Mineokamaki, the birthplace of dairy farming, the importance was shifted from breeding horses to the rearing of cattle. The Mineoka area grew into a great modern dairy farm and produced dairy companies one after the other which would later on drive the Japanese economy. The maki of the Tokugawa Shogun was transformed into the “Agricultural Kingdom of Chiba” by the people of Bōsō.

Watermelon

The View of Rakkabocchi

01